By Tom Jarvis

As part of our 150th anniversary year commemoration, the NHBA has been combing through old issues of Bar News – and its predecessor publication Bar Weekly – to find important landmarks in our history. In our search, we found a small article about attorney Christopher Seufert and his appearance before the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) in 1995. We decided to delve deeper with him for a retrospective look into that memorable experience from nearly 30 years ago.

Attorney Christopher Seufert, a small-firm practitioner from Franklin, NH, is currently working on his 39th year of practicing law. Back in 1987, he took on a case as a favor to his friend from the Knights of Columbus. Little did he know, it would prove to be an arduous adventure lasting several years, that would eventually bring him to the highest court in the land.

“If you were to ask me to take that case now,” Seufert ruminates. “I would slam the door in your face and say no way. I put thousands of hours into that, with all the Federal Court appeals, the US Supreme Court, back to Merrimack County Superior Court – oh my God, I lost my shirt on that.”

His clients, William and Norinne Field, had sold a hotel, Mascoma Lake Lodge, to an investor, Philip Mans, who gave them some cash and seller-financed the rest.

“In the financing documents, it said that Mr. Mans shall convey no equitable or legal portion of this hotel to anybody unless he paid our people off,” Seufert says. “After some time, Mans filed bankruptcy, and in the bankruptcy court proceedings, it turns out he had added a partner, DeFelice and Sons, and conveyed an interest in the hotel. When the Fields had previously asked Mans who DeFelice was, he told them it was just someone who worked for him.”

Seufert argued that Mr. Mans had committed fraud against the Fields, and as a result, the debt should be non-dischargeable. The court disagreed, stating that while it was fraudulent, the plaintiff could have caught it by performing a title search.

“This began a long torturous journey up through the federal court system,” Seufert recalls. “We appealed and lost, so then we asked the US Supreme Court to weigh in on a petition of certiorari. They agreed to accept the case because there was a split in the US between the circuits as to whether the standard is reasonable objective prudent person or justifiable reliance under all the circumstances. We were arguing justifiable reliance under the circumstances because we had no reason to believe there was fraud.”

As very few cases get accepted on certiorari, Seufert was surprised that the SCOTUS agreed to hear the case.

“I dropped my jaw when I got notice that they accepted our case,” Seufert says. “It’s like winning the Megabucks. Now we are in it for real.”

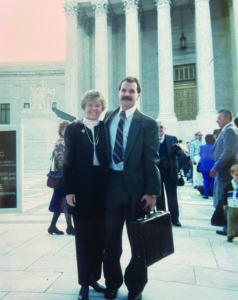

Seufert recalls going down to Washington, DC early to visit family in the area and to prepare himself

“I spent the whole day walking the [National] Mall, wondering what they were going to ask me. I don’t know how many times I went from one end to the other,” Seufert says. “I came up with a half a dozen questions and wrote them on index cards. On the other side, I wrote what my answers would be. And sure enough, every question I thought of, they asked me.”

He remembers that he was nervous the whole day until the green light signifying it was time for his oral argument went on in the courtroom. At that point, he cleared his mind and thought of it as “go time.”

“One question I remember was Ruth Bader Ginsburg asking the difference between overt fraud and subversive fraud,” Seufert recalls. “I had written that as a possible question on one of my index cards, and on the back, I had written the words SHELL GAME.”

The words evoked a time when young Seufert was on military leave and lost $10 to a man playing a shell game in Boston Commons.

“I told the story to Ruth Bader Ginsburg,” Seufert says. “The guy has three cups, and he’s got a shell that he’s palming. He pretends to put the shell under the cup, but it’s in his palm. He moves the cups around, and you try to keep track, but there’s no way you can win because there is no shell. That’s overt fraud. And that’s the difference between overt and subversive fraud – the game you can’t win and the game you might be able to win. When I finished the story, she kind of nodded.”

The Court agreed it was justifiable reliance and remanded the case back to the bankruptcy court.

“I only had 20 minutes because the US Solicitor General had said they wanted some time to argue on the plaintiff’s side, so I yielded 10 minutes to them. They went in a totally different direction, but my 20 minutes was enough. Although, it felt like an eternity up there.”

After SCOTUS remanded the case, it went on for another few years. The bankruptcy court ruled in favor of the defendant once again, so Seufert appealed to the Federal District Court.

“And then we lost again and had to go to the First Circuit again. It was the fifth trial on the case,” Seufert says. “Finally, the First Circuit had enough of me and said, ‘yeah Chris, you win, just get out of our courtroom.’ They remanded it with a finding in our favor and the bankruptcy judge had to just sign it.”

Seufert then filed an action against Mans in Merrimack County Superior Court.

“The judge finally gave us a verdict for the balance plus interest and costs,” Seufert says. “And then we had a couple payment hearings where he kept lying about his assets. Finally, someone called me up and told me that Mans was hiding an expensive sports car in his garage, so I went back with an ex parte and told the judge about the asset.”

With the help of the Sheriff’s office, a tow truck, and a crowbar, they were able to seize the sports car and subsequently auction it off.

“We got paid, but it took us 10 years,” Seufert says. “They were salt-of-the-earth people and Mans just took advantage of them. He was found ‘dishonest’ by the Federal Court.”

After appearing before SCOTUS, Seufert was given a quill feather as a keepsake. He currently has it framed in his reception room with the order on the petition for certiorari.

“They gave my then partner, Attorney [William] Shultz, one of the quill feathers, too,” Seufert says. “He sat at counsel table wiping my brow while I was sweating Twinkies.”

When asked how he would advise someone appearing before SCOTUS today, Seufert jokes around, saying, “avoid it. You’re never going to get paid for the time you put in.”

Seufert says he does recall giving some advice to insurance defense attorney Kate Strickland when a plaintiff’s appeal against her defendant was accepted by SCOTUS 10 years ago.

“She asked how I got into the US Supreme Court,” Seufert says. “I told her oh, it’s just down I95 South.”

After a round of laughter, I asked Seufert what would happen today if one of his client’s wanted to appeal to SCOTUS.

“I would do it again in a heartbeat,” Seufert says. “At a certain point in your career, you only have so many marbles left in the vase to use, and I would use a marble to do that in a heartbeat.”