New Hampshire’s Five Longest-Practicing Attorneys Share Insightful Anecdotes From the 1950s Until Today

By Scott Merrill

Three hundred and twenty-seven years—that’s the combined amount of time New Hampshire’s five longest practicing attorneys have been at it.

Since the 1950s, George Walker, Victor Dahar, Bob Welts, Al Casassa, and Jack Middleton, have been serving their clients through multiple generations and shaping the legal landscape of New Hampshire. While each of these men are slowing down in their own ways—Dahar comes in at 7:30 a.m. these days rather than 6:00 a.m. as he did for years—each of them continues to enjoy going to work.

As we spoke, each one helped me to understand what it was like to live and work in New Hampshire’s legal community long before I was born.

Jack Middleton

Rockingham County over teacher decertification and firings. Middleton represented those in the

teacher’s union. Louis Soule, far right, represented the district.

Jack Middleton, who celebrated his 93rd birthday in January, grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia and came to New Hampshire, ultimately, because of his love of the mountains.

His formative alpine experiences came when he and his brother were sent by their parents to summer camp in Maine because of the polio epidemic in the 1930s.

He recalled hikes up Mount Chocorua in New Hampshire’s Sandwich Range as part of his time spent with the camp, and it was the mountains that led him back to New England for three summers to work for the Appalachian Mountain Club, while attending Lafayette college in Pennsylvania, and as a caretaker at a building in Tuckerman Ravine.

During law school at Boston University, Middleton returned to the Appalachian Mountain Club to run Dolly Copp campground, and then spent a year at the Mount Washington Observatory.

“Twenty days up and 10 days down,” he says, referring to his time spent working at the observatory. “I learned that I wanted to stay in New Hampshire, but I didn’t want to make a career out of working up there.”

Middleton was hired by John McLane Jr. in 1956, and he became the tenth lawyer to work at the firm that bears his name today, McLane Middleton. Today, the firm employs over 100 attorneys specializing in over 30 areas of practice, and has offices in Manchester and Boston.

In the early days, Middleton says he had a general practice, as was the case with many attorneys at the time.

“The idea was to do everything. I did wills and deeds, litigation. Whatever came up.”

His base salary in 1956 was $3,800 a year with a 10 percent end-of-year bonus.

“Dollars then versus dollars now are totally different,” he says. “My friends from law school were making the same at big firms in Boston.”

Middleton tried his last case in 1987 due to hearing trouble but says his primary interest has always been in litigation.

“We tried a lot more cases in those early days, but over the years the area of civil litigation has shrunk tremendously,” he says. “Mediation has really put a dent in the ability for young lawyers to get trial experience. Everything settles.”

He recalled trying “fender bender” cases where he had the opportunity to spend a lot of time with lawyers from Sheehan Phinney or Devine Millimet, and it was during these interactions, he says, that he formed lasting bonds with other attorneys.

“[T]hey had big insurance company clients and we’d battle it out,” he says. “We didn’t have this mediation. We’d all be talking about the case, and a lot of cases settled between the preview statement and sitting down and starting the trial. That has disappeared now.”

One of the memorable cases Middleton litigated was the “license plate case,” or Maynard v. Wooley, in the late 1970s.

“The state of New Hampshire, in its wisdom, passed a statute that said license plates will contain the words ‘Live Free or Die’ and I represented a gentleman by name of Maynard who said he wasn’t comfortable with that because it violated his religious beliefs,” Middleton says.

George Maynard, a Jehovah’s Witness, objected to the state motto on his license plate for religious reasons by affixing a piece of red tape over it. For this action, he was cited multiple times. The first time, a judge fined him $25. The second time, a judge cited him for a $50 fine and, after Maynard refused to pay either fine, sentenced him to 15 days in jail. He was then cited a third time.

“Before I got involved, [Maynard] had spent 15 days in jail for masking the words on his license plate. Some kids had torn the tape off and then [Maynard] cut it off with shears,” Middleton says. “Every time he drove into Littleton the cops would pull him over.”

The Maynards subsequently filed a federal lawsuit that sought a declaratory judgment that the New Hampshire scheme violated the First Amendment. A three-judge Federal District Court entered an order, which prohibited the state from punishing the Maynards.

“The case was tried in Federal District Court in Concord and the Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, Judge Coffin, fortunately found in our favor,” Middleton says.

The state of NH appealed directly to US Supreme Court, but the Court found that it was a classic case of compelled speech and to this day people are not required by law to display the state motto.

Middleton, who continues to work with clients today, was instrumental in establishing the Interest on Lawyers Trust Account program that has enabled the New Hampshire Bar Foundation to provide tens of millions in funding for civil legal services for the poor and for education about the legal system.

And he still gets out in the mountains as much as he can when he’s not in the office.

“I really enjoy the practice of law because I like people and the issues are always challenging; that’s why I still come to the office,” he says, reflecting on his career and the changes he has experienced over time. “The people you’re going to go talk to are old friends of mine and the Bar was much smaller when I first started. You got to know people.”

One of those old friends was H. Alfred “Al” Casassa, who was admitted to the Bar two years after Middleton, in 1958.

H. Alfred “Al” Casassa

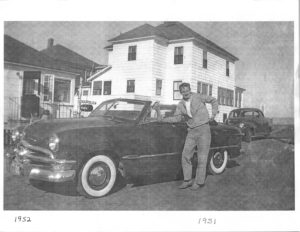

shore), circa 1951.

Casassa spent his first two years as a lawyer with the Internal Revenue Service as a Federal and State tax attorney. In September of 1960, he opened his office at the same location where we sat for an interview at Casassa Law on Main Street in Hampton.

Casassa spent his first two years as a lawyer with the Internal Revenue Service as a Federal and State tax attorney. In September of 1960, he opened his office at the same location where we sat for an interview at Casassa Law on Main Street in Hampton.

Over the years, Casassa has worked with a number of attorneys, including John Ryan and Joseph Mulhern, and today he works alongside Peter Sari, Lisa Bellanti, and his son Bob Casassa, whose son Matthew is an attorney with Foley Hoag in Boston.

“That’s three generations and I’m quite proud of that,” Casassa says.

At 91, Casassa hasn’t ventured far from home—indeed, he’s in the same building where he began more than 60 years ago, attached to where his parents’ store was—and his commitment to Hampton and the people living there has shown throughout the years with his work as a lawyer and in his community service.

He has served as a member and chairman of the Hampton planning board; town moderator for 20 years; director and vice chairman of the Board and legal counsel for the former Hampton Cooperative Bank (now TD Bank); director of Hampton Beach Chamber of Commerce, to name just a few of his roles in the community.

In 2018, Casassa received the New Hampshire Bar Association’s Vickie Bunnell award. Instituted in 1998, the award honors the memory of Vickie M. Bunnell, “A Country Lawyer.” The award is presented to an attorney from a small firm who has exhibited dedication and devotion to community by giving of their time and talents, legal or otherwise.

Casassa’s choice to become an attorney has its roots in the community that he has continued to serve throughout his long career and in his parents’ store, Colt News, where he grew to make connections with people in his community. It was also shaped by one of his neighbors, John Perkins, the father of a childhood friend who lived on Dearborn Avenue in Hampton where he grew up. Perkins was a well-known attorney in Exeter and Judge in Hampton, and Casassa says he looked up to him from a very early age.

“I’ve always been very interested in the community from an early age growing up in the store,” he says.

When Casassa began as an attorney, the town of Hampton was a dry town, and a major portion of the beach was leased to a company called the Hampton Beach Improvement Company as part of a 99-year lease for $100 per year.

In 1983, serving as town moderator, Casassa appointed a committee to study the question of leased land and asked them to report on their findings. As a result of their report, a warrant article at town meeting was voted on to sell the land to the lessees.

“All of the land, instead of being leased to individuals or the improvement company was then sold and the town got millions of dollars for it, but it was sold at 30 percent of the then fair market value,” Casassa says. “It was more than fair to the lessees.”

Today, Casassa is comfortable taking on cases ranging from estate planning, probate, and real estate conveyance, as well as providing business advice to clients and friends. He has tailored his practice so that he no longer has a court calendar and says he has a “marvelous staff.”

“Here I am. This is my situation. I’m partially hearing impaired and not fit for court,” he says. “I have a desk practice and I bring a lot of institutional knowledge about the community and the practice, and I have three generations of clients. I’ve been very blessed. Jack will tell you the same, I’m sure.”

Robert B. Welts

The year before Casassa was admitted to the Bar in New Hampshire, Robert B. “Bob” Welts, who will turn 89 in June, was starting work as an attorney in Nashua. Welts, who is well known in Nashua, has put in many hours as an attorney, a tennis player, and as a runner.

“I went out for track in the tenth grade and I was a little pip squeak,” he says. “I probably went into law school at five-foot- one.”

Welts, who is from Milton Massachusetts, graduated from Boston College Law School in 1957, attending law school alongside his father, an adminstrator the Federal Milk Market Association in Boston.

“I was proud of him,” Welts says, recalling that his father drove to the law school after work in the evenings and finished in four years.

Welts recalls hearing a lecture as a senior in law school by Professor Moynihan that influenced his decision to move to Nashua, where he has been practicing law for over 60 years.

“He said, ‘you Dorchester boys, all you think about is graduating and practicing in Boston. But I say to you, go west.’”

Soon after hearing this, Welts encountered a notice at the law school that Kenneth McLaughlin, later Associate Justice McLaughlin of the Nashua District Court, was looking for another attorney.

“My senior year I would come up on Saturdays and work for him,” Welts says. “Eventually I took two exams 10 days apart. I hadn’t studied but I passed the New Hampshire and the Massachusetts Bar within ten days of each other.”

Mandatory service existed at that time following the Korean war, and Welts joined the New Hampshire National Guard. Having passed his Bar exams only days before, he left for basic training in San Antonio for six months flying out of then Grenier Airport in Manchester.

Upon returning, he began a career in Nashua practicing law, mostly land-use, estate, and probate. In 1977, Welts bought office space that opened when Blakes restaurant on main street in Nashua closed and in 1980 he met Jack White, who became a partner in what has become Welts, White and Fontaine.

“In Nashua, it was mostly solo practitioners then. I think there were 39 attorneys altogether in the town,” he says. “It grew out of nothing.”

Throughout his life, Welts has done a lot of running. In his seventies, he competed in over 65 races each year across the state and he ran a 5k in starting in downtown Hollis just this month.

His three events were primarily the 5k, the 10k, and the 1500, and for five years he finished in the top three, which qualified him for the nationals in cities across the country.

As our time together came to an end, he recalled working with Kathy Powers, who became his legal assistant for nearly fifty years. Powers died following a skiing accident at Waterville Valley.

“She had the fastest and best shorthand I’d ever seen in a person,” Welts says, explaining the two became friends when he and his wife had a son and bought a place at Waterville Valley where Powers became a “beautiful” skier. “For fifty years, she took all of my notes and always knew what to do.”

Welts, who was widowed in his mid-seventies, has a son and two grandchildren, who he continues to spend time with when he’s not attending CLEs or helping clients and friends with legal issues.

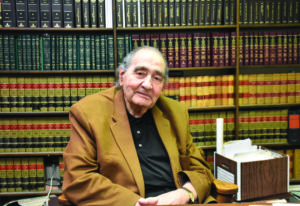

Victor W. Dahar, Sr.

Victor Dahar comes off as a pragmatic man with a good sense of humor and a lot of gratitude. When asked what advice he has for younger attorneys to maintain health and wellness he said:

“Oh, I don’t know. Get an annual physical. Go see a doctor when you’re not feeling good, and keep your fingers crossed. I’ve been lucky,” he says, adding that he still gets up early to get into work. “I’m 92 years old, but I’m in here every day early in the morning until 4 or 5 o’clock. I used to come in at 6 a.m. and now it’s 7:30. Point is, when you get in the habit of getting up early you can’t break that habit.”

Dahar has been in his office on 20 Merrimack St. in downtown Manchester for 35 years. Of his four children—two sons and two daughters—three became lawyers and work with him today, while one of his daughters works for Athenahealth in Boston.

“I encouraged my daughters and sons to go to law school and now I have the pleasure of seeing them every day of the week when I go to work,” he says. “A lot of people see going to work as something they have to do. We go to work because we enjoy it.”

After attending Boston College Law School, Dahar passed the bar in 1958 and went to work doing primarily bankruptcy cases. “At that time, there were 15 people, I think, who passed the Bar and I recall in 1958 the total membership was around 600 lawyers for the whole state. Today, it’s closer to 8,000.”

Dahar’s weekly income in 1960 was roughly $100 per week, he recalled, adding, “You could go to lunch for a dollar and a quarter and have the best lunch in the world.”

“And everyone knew everyone. Those relationships don’t exist as much. Fellow members are chasing the dollars.”

In the late 1950s, Dahar met Joe Bentley, a bankruptcy referee who suggested he rent an office from him. In those days, bankruptcy cases were not handled by judges, he explained.

“From that time on, I’ve been sitting here doing the same thing,” Dahar says. “As a matter of fact, by being in Joe Bentley’s office, I was appointed the chapter seven trustee and I’ve been the chapter seven trustee for the last 60 years.

The reward, even at this age, is getting a lot of people over the years letting me know how happy they are with the work we’ve done for them.”

George W. Walker

While many people retire around age 65, this wasn’t the case for George W. Walker. Barred in 1954, Walker is the longest-practicing attorney in the state.

One of five children, Walker grew up in Newton and Concord, Massachusetts, and later Durham, New Hampshire, where he lived on his parent’s farm.

After graduating from Dover High School, he attended UNH, where he studied liberal arts. But “study” may not be the best word to use. After his first year, he flunked out of school and went to work at a shoe factory.

“At the end of freshman year, when I was ‘invited not to come back,’ I went over to Claremont to work at a shoe manufacturing company,” he says. “That encouraged me to get back to school.”

Walker made the dean’s list each year after his freshman year and eventually went on to study law at Northeastern for one year, and then Boston University, where he made law review and graduated Cum Laude in his final two years.

Asked why he chose law school, Walker says he was “shunted into it by a friend” studying law at Boston College while he attended UNH.

His first year at Northeastern Law School was a success but Walker, who was working as a short order cook at McManis’s restaurant at the time, found Boston University to be a better fit.

After graduating with his J.D. from Boston University, Walker went to Liberty Mutual in Boston, where he worked for a year before fulfilling his draft commitment in Charlotesville, N.C. While in the Army he applied for a commission in the JAG Core, was accepted in the infantry officers training school, JAG school, and received his student’s pilots license on the side.

From Charlottesville he was assigned to a small office in Paris where he served as a liaison with the French Army, filing damage claims. He also was married while there.

Upon returning to the United States, Walker made his way to Wolfeboro after a tip from a law school friend about a possible job with Jim Calan.

Still in the Army, and living at his wife’s brother’s house in Melrose, Walker remembers thinking, “Wolfeboro?” with some skepticism.

“But it was an idyllic village, and Jim was a scholar. His office had a lot of bookcases, and knotty pine paneling, and carpeting,” Walker recalled. “Not only did he have all of the NH Reports, he had all Supreme Court decisions and Federal First District Court decisions. As good as I’d seen in in Manchester or Boston. He employed me and I went back to Virginia and submitted my resignation.”

After commuting for years between Wolfeboro and Rochester, where he worked for Dick Cooper and Fred Hall, he eventually moved to the place he is at today, where he has practiced in various areas of law. He says criminal defense work was his favorite, referring to it as “a game between you and the prosecutor.”

“Your job as a defense attorney is to see that your client has all the constitutional protections and that the State proves their case beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Walker says there weren’t many negotiated pleas in his early days and that he enjoyed going to trial. But the roles were reversed when he was elected county attorney.

“I became the prosecutor, and I was told by presiding justices that they would allot me two weeks of jury time each term,” he says. “I’d have 25 cases or so. The Judge would say you need to pick guilty pleas by agreement. I would select the best chances of proving guilt early on that would encourage defense attorneys to make a deal.”

He spent three years at the county attorney’s office, which was a part-time job, and then focused on his own practice, representing clients with property disputes over tax liens and a variety of other matters.

Many of his clients today are intergenerational.

“I still have clients who need my help, and I keep busy,” he says, recalling the formation of a trust that has progressed into the fourth generation with over 125 people.

When he’s not in the office, Walker spends time tending to his vegetable garden, splitting wood, stacking hay, seeing his daughters and grandchildren, and until recently, taking care of his horses. He also enjoyed playing competitive tennis at the Wolfeboro country club until he was 87 and a shoulder injury forced him to stop playing.

“I find it a little disconcerting to think about what I’d be doing if I weren’t coming in,” he says, adding that he’s cut back to working three days a week. “I look forward to coming into the office. I’m good at what I do and I’m a competitive person. That’s why I did so much trial work. I’m a problem solver and I like to feel useful.”