By Tom Jarvis

On August 11, 2023, more than 50 people, including judges, lawyers, media representatives, and three generations of family members from across the country attended the portrait unveiling ceremony of Judge Ivorey Cobb, the Granite State’s first African American jurist, at the New Hampshire Supreme Court (NHSC). His portrait is now on permanent display at the highest court in the state, just outside the law library.

The idea to honor Judge Cobb stemmed from a conversation between NHSC Senior Associate Justice Gary Hicks – whose family was friends with the Cobb family in Colebrook – and NHSC Chief Justice Gordon MacDonald.

“Judge Cobb was a trailblazer among New Hampshire jurists,” Justice Hicks, who served as the master of ceremonies, said at the event. “As the first African American jurist in New Hampshire, Judge Cobb was committed to equal justice under the law. This was not just a professional standard for Judge Cobb; instead, it was the calling of his lifetime. He was a true believer in the ideals of America and was determined to make his community and his country a more perfect union.”

After some brief remarks from NHSC Society President Doreen Connor, Chief Justice MacDonald then took the podium.

“On the walls of this room and throughout this building, we acknowledge and honor those who have served our state in the advancement of justice. We are surrounded by the images of some true giants of the law – innovators, pioneers, and pathbreakers. They remind us of the rich heritage we share, and they inspire us to be worthy of it. Judge Ivorey Cobb is exactly such an innovator, pioneer, and pathbreaker. He served the United States, the State of New Hampshire, and his community with great distinction. We honor this man and his career today by adding his image to our walls.”

Ivorey Cobb was born in Alabama on September 28, 1911. After attending Duquesne University in Pennsylvania, Cobb began a career in journalism at the Pittsburgh Crusader. In 1937, he founded and began publishing the Pittsburgh Examiner. After marrying his wife, Elsie (Stanton) Cobb in 1938, she worked there with him to distribute the weekly editions. He later worked with the Chicago Defender to create the National Negro Publishing Association, now called the National Newspapers Publishing Association.

In 1942, he joined the US Army, where he served as a logistics officer during World War II and the Korean War. Throughout his military career, he received numerous commendations, citations, and medals for meritorious service and eventually earned the rank of Major. He also continued to pursue further undergraduate and graduate studies at Rutgers University, Northeastern University, and the University of Maryland Overseas Division in Austria and Italy.

In the late 1950s, while stationed at Fort Devens in Massachusetts – and working as the editor of both the Fort Devens Dispatch and the Camp Drum Sentinel – he began attending the Suffolk University School of Law. In 1960, he earned what was then known as a Bachelor of Law degree, or LLB. (In the mid-to-late 1960s, the American Bar Association encouraged law schools to upgrade the name to juris doctor to reflect the postgraduate status of the degree.)

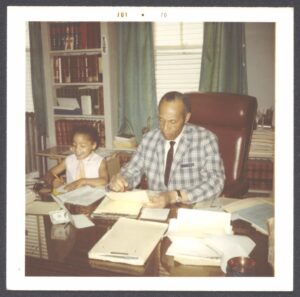

“When he was attending classes in law school, while finishing up in the military, he would drive almost an hour home to Harvard [Massachusetts] from Fort Devens in his little Volkswagen Karmann Ghia, grab a sandwich, and then drive an hour to Boston to attend classes. It was a grind,” Louise Cobb Phillips says. She is the youngest of Cobb’s three daughters. “There were times when we all would go to the law library in Boston. My sisters and my mother would all be grabbing books and whatever was needed to help him research cases. It was a big family affair.”

Cobb retired from the military in 1962 and opened a law practice in his hometown of Colebrook, New Hampshire. Two years later, he was nominated by then-Governor John W. King to become a Special Justice of the Colebrook Municipal Court. His appointment made national news the next day, including coverage in the New York Times.

“It was really huge,” Phillips says. “Especially because he was a Black attorney and judge in a community where we were the only family of color. That’s why it made national news.”

In 1965, Judge Cobb received an honorary JD from Suffolk University School of Law, and in 1968, he was confirmed as a judge of the Colebrook District Court, where he served until his retirement in 1981. He also served on the New Hampshire Commission on Civil Rights.

Judge Cobb passed away in December 1992. Less than a year later, in August 1993, his wife Elsie died.

In the mid-1970s, Judge Cobb’s eldest daughter, Marilyn Cobb McDonald, began attending North Carolina Central University School of Law. While she was away, her daughter Marilyn would stay with the Cobbs in Colebrook.

“I was the first grandchild, so I had him basically monopolized until my cousin Edmond was born,” Judge Cobb’s granddaughter Marilyn McDonald Hendricks says. “Granddaddy was a lot of fun. He would skip down the street with me, singing ‘Skip to My Lou,’ and he would race me across the yard. Sometimes he’d let me win and sometimes he didn’t. He also built me a launching pad on a huge snowbank for my red flying saucer and would sometimes actually get in the saucer with me.”

Hendricks remembers how Judge Cobb often taught her critical thinking by having her solve riddles and how he taught her lessons in fairness with the use of snacks.

“For example, Granddad liked pomegranates and his rule was that whoever cut it, the other person got to choose which half they would get,” she says. “So, if you tried to cut it unevenly, thinking you were going to get a bigger piece, that’s not going to happen because the other person gets to decide which one they want.”

Hendricks says Judge Cobb was a brilliant intellectual with a great sense of humor and that he was “unapologetically proud to be part of the African American community.”

“His philosophy of going where the opportunity is has led our family to so many different places and taught us that you can be a great representative of your community no matter where you go,” she says.

Hendricks’ mother earned her JD in 1977 and clerked for Judge Cobb for a while before moving back to Pennsylvania with her daughter. There, she practiced housing law for a few years before moving to Illinois and then later to Washington, DC, where she worked for then-US Congressman Louis Stokes on the House Committee on Appropriations. In December 2015, Marilyn Cobb McDonald passed away from pancreatic cancer.

Hendricks says that because her mother was a lawyer, she felt she was also representing her when she spoke at Judge Cobb’s portrait unveiling ceremony.

Other speakers at the event included New Hampshire Bar Foundation Chair Scott Harris, NAACP Manchester President James McKim, Congresswoman Annie Kuster, representatives from the offices of Senator Jeanne Shaheen and Congressman Chris Pappas, and Circuit Court Administrative Judge David King.

Judge King, who went to elementary school with Hendricks, said Judge Cobb had a reputation as a law-and-order judge who could be tough on sentencing criminal defendants.

“Judge Cobb’s secretary and his clerk of court was Joan Shatney,” Judge King said. “After Judge Cobb retired, she came to work for Phil [Waystack] and me [at Waystack & King] as my first legal assistant. I would hear pretty much every day from her, ‘this is how Mr. Cobb would do it.’ So, through Joan Shatney, I learned the Judge Cobb way.”

Just prior to the portrait unveiling, as Hendricks spoke of her grandfather’s philosophies and achievements, she described how his empathy toward juveniles resulted in a creative diversion tactic for them.

“He strongly believed that just like reporters, lawyers must also possess a strong respect for words, and that advocacy must rest upon a strong factual foundation,” Hendricks said at the event. “He always insisted that we get all the facts from multiple sources to support educated decision making. He believed that words mattered so much that he included writing assignments in his innovative and potentially controversial today – as well as then – method of sentencing for juveniles. They had the chance of either going to jail, doing community service, or attending a church of their choosing. The church option required weekly 100-word essays signed by the minister. Many of the juveniles attended Sunday school classes, which were taught by Janice Hicks, Justice Hicks’ mother.”

Hendricks continued: “Judge Cobb believed that these sentences were opportunities to divert some juvenile defendants from becoming hardened criminals. Many years later, on Main Street, a Colebrook prior offender shared with [my aunt] Louise that Judge Cobb had saved his life by sending him to church.”

Near the end of the ceremony, Judge Cobb’s daughters, Louise Cobb Phillips and Gretel Cobb Webster, pulled a black canvas off the portrait to reveal it. Neither daughter spoke to the audience at the event, knowing fully well that they would not make it through without breaking down in tears. However, once the portrait was unveiled, Webster softly said, “that’s daddy,” and the two of them wept.

“I was very touched by all the wonderful things that everyone had to say about my father,” Phillips says. “All our lives growing up in that household, we knew that he was exceptional and that’s just the way it was. This was the acknowledgement of his exceptionalism and just what it took from his humble beginnings in Alabama to becoming a district court judge in New Hampshire. My father would be very proud. It’s overwhelming. A good overwhelming. Just thinking about it brings tears to my eyes again.”

Attorney Phil Waystack, who briefly worked at Judge Cobb’s law office, describes Cobb as a very dignified and charming man who laughed a lot and always wore a suit.

“Ivorey Cobb was the reason I came to New Hampshire – and 49 years later, I’m still here. He gave me the opportunity to move to this state and develop a practice,” Waystack says. “It’s kind of a sobering thought that in 60 years, he’s been the only Black judge in the state. But that simply underscores what a pathfinder he truly was. In a way it’s sad that it took so long until another person of color got on the bench, too. She’s a magistrate judge [US Magistrate Judge Talesha Saint-Marc], but she’s still in a judicial position,” he says. “It would be nice if we could have more diversity on the bench.”

Waystack says he thinks it’s terrific that Judge Cobb’s portrait is now a permanent fixture at the New Hampshire Supreme Court.

“I greatly appreciate the fact that Justice Hicks led the effort to do this, that the Supreme Court felt it was important enough to have a reception, and that the Bar Foundation supported the effort,” he says. “I encourage it and I hope it portends the beginning of a more diverse bench for the State of New Hampshire.”