By Tom Jarvis

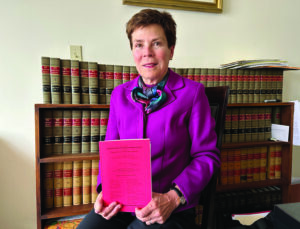

For Exeter attorney Terrie Harman, appearing before the US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) for the first time on April 24, 2023, was exhilarating. It’s a great privilege and a rare opportunity to appear before SCOTUS, and that is not lost on Harman.

“It’s every lawyer’s dream to go to the US Supreme Court,” she says. “It was incredibly exciting. I can hardly believe that I went.”

Harman graduated from Franklin Pierce Law School in 1978 and began working at Pine Tree Legal Assistance in Bangor, Maine. There, she learned about bankruptcy law while representing indigents and developed a passion for the Bankruptcy Code. In the 1980s, she started her own firm, Harman Law Offices, where she was heavily involved in bankruptcy litigation and later became a Chapter 7 Bankruptcy Trustee.

Nowadays, her practice is mostly focused on probate litigation, estate planning, and general civil litigation, but it was one of her old bankruptcy cases that caught the eye of Boston lawyer, Richard Gottlieb, leading to a phone call that would place her on a trajectory to the highest court in the land.

Gottlieb was representing a client named Brian Coughlin in a Chapter 13 bankruptcy. Gottlieb assured his client that the harassing, relentless calls from his creditors would cease due to the automatic stay. However, one creditor, an online payday lender called Lendgreen, continued harassing him mercilessly. After many failed attempts to get them to stop, Coughlin became overwhelmed and attempted suicide. Following approximately two weeks of recovery in Mass General, Coughlin sued Lendgreen for violating the automatic stay.

After discovering Harman’s work on the Duby case 10 years ago, Gottlieb reached out to her.

Dorothy Duby was an elderly, blind widow whom Harman represented pro bono in a Chapter 7 bankruptcy. When Duby filed, she had included a debt of $1,800 to the US Department of Agriculture, but the USDA continued to harass her. Duby became despondent and fearful.

“It scared the dickens out of her,” Harman says. “She literally thought the whole force of the US government was going to come down on her.”

With Harman’s help, Duby sued the USDA, claiming emotional distress damages for their violation of the automatic stay. The First Circuit ruled that emotional distress damages were not allowed for violation of the automatic stay by the Sovereign. As there was an apparent split in the circuit courts on the matter, Harman petitioned the US Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari, but it was denied.

Realizing his client, Coughlin, had a similar legal issue to Duby – with respect to emotional distress damages – Gottlieb asked Harman to get involved.

“What’s more emotionally distressing than trying to take your own life?” Harman asks rhetorically.

In Coughlin’s case, Lendgreen filed a motion to dismiss, citing tribal immunity because they are a subsidiary of Lac Du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians (the Tribe), a federally recognized Native American tribe. The Bankruptcy Court agreed with Lendgreen and the Tribe and dismissed the case, favoring a Sixth Circuit decision on the issue.

“We were successful in leapfrogging over the next appellate court and got ourselves handsomely into the First Circuit Court of Appeals,” Harman says. “I’ve been in the First Circuit more than once, but I knew this case had huge ramifications, and it deserved and needed the expertise of counsel who is very experienced in matters potentially going before the US Supreme Court. Rick [Gottlieb] and I did not fit that bill, so I called Greg Rapawy.”

Gregory Rapawy, a partner at Kellogg Hansen in Washington, DC, is no stranger to the US Supreme Court. After law school, he clerked for Justice David Souter and has previously argued before the Court on another case.

Just as Gottlieb found Harman in connection with Duby, Harman found Rapawy due to his work on another bankruptcy case called Greek Town, which also involved the issue of abrogation of tribal immunity under the Bankruptcy Code. The Sixth Circuit had decided against Rapawy’s client, so he sought certiorari from SCOTUS, but the case settled while it was pending.

“Once Terrie realized she had this same issue, she called me up to ask if I had any thoughts,” Rapawy says. “I told her that if she was interested, I would be willing to participate in the First Circuit appeal. Obviously, we didn’t know at the time that it was going to the Supreme Court.”

The First Circuit reversed the Bankruptcy Court, siding with the Ninth Circuit’s conclusion that the Bankruptcy Code distinctly abrogates tribal sovereign immunity. The Tribe then filed a petition for a writ of certiorari from the US Supreme Court, and it was granted in mid-January 2023.

The Bankruptcy Code abrogates sovereign immunity with respect to the automatic stay. The Code further provides a broad definition of “sovereign” to include all governments, foreign and domestic; however, it does not specifically mention Native American tribes. The Tribe argued that since Native American tribes are not listed, they are excluded.

The federal courts are split on whether this language explicitly expresses Congress’s intent to nullify tribal sovereign immunity.

“This kicked back to what I learned in law school about statutory construction,” Harman says. “I never thought I would have any use for statutory construction, but here I am, all these years later, remembering those classes and learning a lot about how to construe what Congress intended. The Tribe is saying, ‘we’re not listed; therefore, we’re not really included,’ and we are saying ‘there’s no magic words requirement for Native American tribes.’ The law is clear: it abrogates immunity for all governments, foreign and domestic – and that includes the Tribe, as a government.”

Four Amicus briefs were filed on behalf of Coughlin, including one by retired US Bankruptcy judges Judith Fitzgerald (PA), Joan Feeney and Carol Kenner (MA), Phillip Shefferly and Steven Rhodes (MI), and Eugene Wedoff (IL), as well as one by the Office of the Solicitor General.

“This was just beyond the usual, everyday practice of me sitting here in Exeter, New Hampshire,” Harman says. “I get a call from Greg Rapawy saying we’re on for a call with the Solicitor General [Elizabeth Prelogar] and let me tell you, I grew an inch. There were 31 lawyers from the Federal government on that Zoom.”

After the call, the legal team of Harman, Rapawy, and Gottlieb agreed to cede 10 of their 30 minutes allotted before the Court to Assistant Solicitor General Austin Raynor.

In preparation for their SCOTUS appearance, the team participated in several in-house moot arguments, including one with retired US Bankruptcy Justice Joan Feeney and another with G. Eric Brunstad, Jr., a partner from Dechert, LLP, who has argued 11 SCOTUS cases and worked on more than 35 other SCOTUS matters.

On April 24, 2023, the morning of her first-ever SCOTUS appearance, Harman went for a jog and discovered a back door into the building.

“There I was in my running clothes, sneakers, and baseball cap, and I spoke to a nice security guard there and told him I’m part of the arguing counsel team. I asked if it would be okay to come in this back door later,” Harman says. “He said, ‘oh sure, come on in the back door.’ So, I was glad to be able to avoid lines out front. I felt like a real Washington insider because I got to go in the back door with special arrangements by the nice security guard.”

Harman and Rapawy expect to hear the Court’s decision by the end of June.

“The Supreme Court has a practice of deciding all the cases for a term before they leave for their summer recess,” Rapawy says. “The Tribe has already said to the Supreme Court that they consider themselves to be bound by the automatic stay. So, we would hope at this point, that they would comply regardless of the result, and that Mr. Coughlin will not be bothered again. If the judgment is affirmed, then we will continue to seek monetary damages in the Bankruptcy Court for his medical bills for the hospitalization incident and his other actual damages.”

Terrie Harman says she learned a lot from the Coughlin case.

“The whole thing has been a tremendous learning experience for me,” she says. “I thought I knew a fair amount about bankruptcy, but I have this whole new understanding about something called, in rem jurisdiction, which we bankruptcy lawyers never even think about. And I have this whole new layer of historical understanding about bankruptcy.”

Harman continues: “Here’s me, a Bankruptcy Code and probate lawyer from Exeter, now wrestling with tribal immunity. It’s been an interesting new area to learn about. I’ll tell you, the humility – I’m humble pie. I thought I knew my way around a lot, but there’s a lot that I didn’t know and had to learn.”

When asked about how she feels now that she’s returned from Washington, DC, Harman says she has a lot of work to catch up on.

“I’m happy and proud of my other clients for being so supportive,” Harman says. “It’s been a team effort with a lot of people: my husband, the other lawyers – even my hairdresser. It’s still so surreal. I think everybody was so affected by the enormity of what we just did. I’m exhausted from the whole thing.”