By Amy Manzelli

This March, 18 environmental attorneys, consultants, engineers, and a reporter convened to provide an update on the latest in environmental law. The following are excerpts from each of their presentations. For many more details, and to earn CLE credits, please log on to https://nhbar.inreachce.com.

State of the State’s Waters

Theodore E. Diers, Administrator, NHDES Watershed Management

Adam Dumville, Esq., McLane Middleton, P.A.

Terry L. Desmarais, Jr., City Engineer City of Portsmouth

While the state of New Hampshire’s waters is much improved over the days when sewage was discharged directly, the current struggle is nutrients. As a result, EPA Region 1 has issued the Great Bay Total Nitrogen General Permit for 13 eligible wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs) that discharge treated wastewater containing nitrogen within the Great Bay watershed (General Permit), effective February 1, 2021. The General Permit establishes total nitrogen effluent limitations, monitoring requirements, reporting requirements, and standard conditions.

To assist with achieving the reductions in nitrogen discharges that the General Permit requires, on April 8, 2021, several Seacoast towns have entered into a novel agreement: the Great Bay Intermunicipal Agreement for the Development of an Adaptive Water Quality Management Plan for Great Bay Estuary. The towns include Dover, Rochester, Portsmouth, Newington, and Milton. Through the agreement, they will work together as authorized by state law (RSA 53-A:1) to perform elements of adaptive management the General Permit envisions. Additionally, the Small Wastewater Treatment Facility General Permit was also finally issued in 2021.

Managing Nitrogen Compliance in Portsmouth: Historic Portsmouth, a tourism magnet with access to waterways, Pease, and more, presents unique wastewater management challenges: Regional Water and Sewer System, Sewer collection infrastructure dating back to the 1800s, with three combined sewer overflows, Storm Drain Collection System, Two Wastewater Treatment Facilities: Pierce Island and Pease, and Downstream of Great and Little Bays and Urban Runoff.

Portsmouth is achieving nitrogen reductions through Best Management Practices, both structural ones, including infrastructure upgrades, bioretention, gravel wetlands, and hot spot mapping; and non-structural ones, including impervious disconnects, leaf litter management, street sweeping, fertilizer alternatives, regulations, catch basin cleaning, and outreach. Now, Portsmouth and the rest of the Seacoast await the response of the Great Bay!

Portsmouth is achieving nitrogen reductions through Best Management Practices, both structural ones, including infrastructure upgrades, bioretention, gravel wetlands, and hot spot mapping; and non-structural ones, including impervious disconnects, leaf litter management, street sweeping, fertilizer alternatives, regulations, catch basin cleaning, and outreach. Now, Portsmouth and the rest of the Seacoast await the response of the Great Bay!

NH Department of Energy: Meet the Place and the People

Rorie E. Patterson, Esq., David J. Shulock, Esq., Joshua W. Elliott, Stephen R. Eckberg, Daniel Phelan

The State’s newest Department is comprised of the Commissioner’s Office and four divisions: Regulatory Support, Policy and Programs, Enforcement, and Administration. Most of the Department’s staff worked for the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) before July 1, 2021. Most of the staff of the Office of Strategic Initiatives moved to the Department on July 1, 2021.

Commissioner’s Office: Jared S. Chicoine is the Commissioner. Christopher J. Ellms, Jr. is the Deputy Commissioner. The staff includes the general counsel, and those who work on external affairs and the department’s website.

Division of Regulatory Support: Regulatory Support advocates for the public interest in energy‐related proceedings, primarily at the PUC, as an automatic party. Division staff includes those who worked in the electric, gas, and water divisions at the PUC. Thomas Frantz is the division director.

Division of Policy and Programs: This division develops and implements policies and programs to achieve an affordable, innovative, reliable, and sustainable energy economy for the State and its citizens. This includes the State Energy Strategy. Policy and Programs administers federal fuel assistance and weatherization funds, the federal State Energy Program grant, and the state’s Renewable Energy Fund. Compliance with the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standards and the state’s Energy Code Program are managed by the division. Policy and Programs Division includes staff doing wholesale/regional electric work, those in the Office of Offshore Wind Industry Development, and the consumer service staff. Joshua Elliott is the division director.

Division of Enforcement: This division investigates compliance with safety‐related laws applicable to electric utilities, natural gas utilities, and pipelines. Department proceedings may result. Enforcement monitors utility cybersecurity plans, oversees the Underground Damage Prevention Program, and participates in emergency preparedness and response. Enforcement maintains a geographic information system for critical and major energy as well as telecommunications infrastructure. The division includes staff who perform financial audits of utility books and records. Paul Kasper is the division director.

Division of Administration: Administration includes legal staff, which primarily support staff in other divisions, in PUC proceedings. The Department’s business office and grants compliance staff are also in this division. The division provides administrative support to the PUC, the Office of the Consumer Advocate, and the Site Evaluation Committee. Rorie Patterson is the division director.

The CLE materials include helpful materials such a list of the laws administered or associated with the NH Department of Energy, as well as discussion of the transition to a decarbonized economy, and how New Hampshire’s goal to that end compare with our adjacent state’s goals.

Offshore Wind: It’s Coming…Probably?

Annie Ropeik, Spectrum News

Mark Sanborn, Assistant Commissioner, NH Department of Environmental Services

Attorney Rebecca S. Walkley, McLane Middleton Professional Association

Globally: The discussion began with the global story of offshore wind, which involves significantly more offshore wind in most other countries compared to that of the United States. This discussion was based on Windfall, from NHPR’s Outside/In, a show about the natural world and how we use it. Windfall is a 2021 five-part series exploring the birth of the new American industry of offshore wind, and who has the power to reshape the future of where our energy comes from. Listen to Windfall at www.outsideinradio.org/windfall.

New England Process 2019 to Now: In January 2019, Governor Chris Sununu requested the Gulf of Maine Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force be established by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). It includes New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine, and all federally recognized Tribes in the Gulf of Maine Region. In March 2021, the Biden Administration announced their commitment to use federal funding and its federal regulatory authority to support their call for the deployment of 30 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind in the United States by 2030. In February of this year, the NH Department of Environmental Services and the NH Department of Energy released a report on greenhouse gas emissions and port and transmission infrastructure in New Hampshire as it relates to the potential for offshore wind in the Gulf of Maine. Currently, relevant NH state agencies are conducting a six-month stakeholder engagement effort to discuss their questions, priorities, and concerns as it relates to BOEM’s siting and leasing process for the Gulf of Maine and the mapping efforts that are part of this process. Nationally, BOEM is developing compensatory mitigation guidance and engaging with Special Initiative on Offshore Wind, a non-profit organization focused on supporting efforts to develop offshore wind in the United States.

For the most part, onshore wind in New Hampshire has been subject to review by the New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee (SEC) pursuant to RSA 162-H and the implementing regulations, including Granite Reliable Wind Farm, Groton Wind, Lempster Wind, and Antrim Wind.

Siting: The Submerged Lands Act (SLA) of 1953, 43 U.S.C. §1301 et seq., grants individual states rights to the natural resources of submerged lands from the coastline to no more than three nautical miles into the ocean (with exceptions that do not apply in the northeast). The result of the SLA, in the context of offshore wind, is that individual states only have jurisdictional authority to review the siting of offshore wind construction to the extent that construction will occur within three nautical miles of the coastline.

Beyond that, the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953 (OCSLA) facilitates the federal government’s leasing of its offshore mineral resources and energy resources.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EP Act) authorized the Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management (BOEM) to issue leases, easements, and rights of way to allow for renewable energy development on the OCS and lays out a general framework, including coordination with relevant Federal agencies and affected state and local governments.

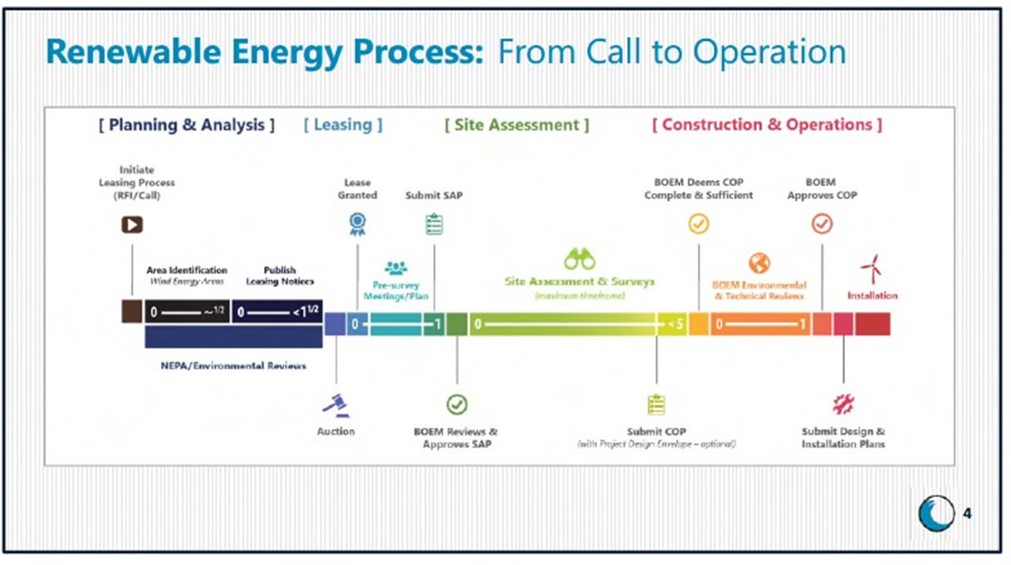

In 2009, the Department of the Interior announced the finalization of regulations governing BOEM’s OCS Renewable Energy Program. See, 30 CFR 585. BOEM, pursuant to its Renewable Energy Program, has a four-step process for permitting offshore wind development on the OCS. BOEM (1) identifies suitable offshore areas for wind energy development; (2) issues leases for development; (3) requests and reviews a site assessment conducted by the leasehold; and (4) reviews the leasehold’s construction and operations plan. At each stage of this process, key stakeholders have an opportunity to provide input and suggestions to BOEM.

Although the SLA limits the authority of individual states to regulate offshore wind projects, that does not mean that offshore wind facilities are going to be completely exempt from state review. While the turbines and towers themselves may not be part of the state review process, elements of the proposed offshore facility within three nautical miles of the shore still may need to go before state review. For example, underwater cables, upgrade to transmission structures, or additional structures to interconnect to the grid may still require state review separate and apart from any review at the federal level.

Although the SLA limits the authority of individual states to regulate offshore wind projects, that does not mean that offshore wind facilities are going to be completely exempt from state review. While the turbines and towers themselves may not be part of the state review process, elements of the proposed offshore facility within three nautical miles of the shore still may need to go before state review. For example, underwater cables, upgrade to transmission structures, or additional structures to interconnect to the grid may still require state review separate and apart from any review at the federal level.

How’s the Sun Shining? The Latest in Granite State’s Solar

Amy Manzelli, Esq. and Julia Nosel, BCM Environmental & Land Law, PLLC

Attorney Rebecca S. Walkley, McLane Middleton Professional Association

Susan S. Geiger, Orr & Reno, PA

Net-metering refers to privately owned solar panels creating energy that powers private homes or businesses or municipal buildings, the excess of which is sold back to the power company for use by other consumers. Net metering is allowed by statute RSA 362-A:9 last updated October 2021. Group net-metering can also be used, in which multiple homes, businesses, and buildings are all connected to the same solar grid, and they share the energy produced by it.

Net Metering Cap: Legislation has been passed recently (HB 315 passed in August 2021, codified at RSA 362-A:1-a, II-c) to allow more power to be generated by municipalities than has previously been permitted. This will prove a great benefit to municipalities and residents alike because it will make it more cost-effective to build a larger grid to power more buildings, which in turn provides benefit to the community. Previously, generators of solar power have been allowed to generate only up to one megawatt of their own power. Now that cap has been raised to five megawatts. Though many feel this still is not enough, the increase from one to five makes an enormous difference for towns like Hanover that are pushing to become more environmentally conscious.

Group Net Metering and Agriculture – Sun Moon Farm Case Study: The potential of group net metering with solar energy may provide a revolutionary way for farms to remain viable. The first example of this in New Hampshire is Sun Moon Farm in Rindge. The Monadnock Region Community Supported Solar project, or CSS, helps local farms benefit from renewable energy through a model that brings together farmers, investors, and community leaders to expand renewable energy and encourage farm viability in their communities. The Cheshire County Conservation District (CCCD) has played an integral role in getting this solar array up and running in cooperation with Sun Moon Farm.

Siting Solar in the State of New Hampshire: Prior to the Chinook Solar Project, which the New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee (SEC) reviewed and granted a certificate of site and facility in 2020, all solar projects in the State were reviewed and either approved or denied at the local level. Municipalities are challenged in evaluating solar projects under traditional zoning ordinances and site plan regulations that are not written with solar in mind. By default, solar power is often lumped in with other energy utilities. Such review could result in solar projects being relegated to industrial zones – even though something like a gas-fired power plant and solar array has little in common from a zoning perspective. As solar becomes more prevalent in the State, however, more municipalities are seeking to adopt solar specific ordinances to allow for easier review of potential solar projects.

Per RSA 162-H:2, VII, “Renewable energy facility” means electric generating station equipment and associated facilities designed for, or capable of, operation at a nameplate capacity of greater than 30 megawatts and powered by … solar … energy. “Renewable energy facility” shall also include electric generating station equipment and associated facilities of 30 megawatts or less nameplate capacity but at least 5 megawatts which the committee determines requires a certificate, consistent with the findings and purposes set forth in RSA 162-H:1, either on its own motion or by petition of the applicant or two or more petitioners as defined in RSA 162-H:2, XI. RSA 162-H:2, XII.

A utility-scale solar project can therefore come before the SEC either because it has a nameplate capacity of 30 MW or more or, because either the applicant or two or more petitioners, as defined in RSA 162-H:2, petition the SEC to assert jurisdiction.

The SEC has taken distilled RSA 162-H:1 as to whether to assert jurisdiction into five main criteria – whether asserting jurisdiction and requiring the project receive a certificate of site and facility is needed to: 1. maintain a balance among those potential significant impacts and benefits in decisions about the siting, construction, and operation of energy facilities in New Hampshire; 2. avoid undue delay in the construction of new energy facilities; 3. provide for full and timely consideration of environmental consequences; 4. ensure the full and complete public disclosure by entities planning to construct energy facilities in the state of such plans; and 5. ensure that the construction and operation of energy facilities is treated as a significant aspect of land-use planning in which all environmental, economic, and technical issues are resolved in an integrated fashion. Order Denying Petition for Jurisdiction, Milford Spartan Solar, Docket No. 2021-01, p. 9-10 (November 10, 2021).

In addition to the SEC’s considerations, to decide between permitting a project of more than 5 MW or less than 30 MW at the local or SEC levels, consideration should also be given to:

- Content of the local zoning ordinance?

- How large is the project?

- What is the capacity of the host community(ies) to review a project of the size proposed?

- What is the relationship like between the applicant and the host communities?

- Does the project involve more than one municipality, and would it require independent review by multiple planning/zoning boards/conservation commissions?

- Will the project require numerous approvals from State agencies?

- Is timing a concern?

Environmental Justice: Lead as a Case Study

Attorney Kerstin B. Cornell, NH Legal Assistance

Attorney Heidi H. Trimarco, Conservation Law Foundation

Lead poisoning is the top environmental health hazard for children in the United States. Children in New Hampshire are at a particularly high risk due to the age of the housing stock in the state. Over 62 percent of homes were built before the interior use of lead paint was banned in 1978. Though lead in water often gets more attention, at least in part due to the Flint water crisis, most children in the Granite State are poisoned by lead paint hazards in their homes. This typically occurs when children ingest lead chips that fall from surfaces where paint has deteriorated or through ingestion of lead dust most frequently created by friction surfaces in older homes. Sometimes this is because of families doing renovations without using proper procedures to prevent exposure to lead dust, most frequently it is due to poor maintenance of older homes.

Impact of lead poisoning on children and the economy: Childhood lead poisoning causes lifelong developmental deficits including Cognitive delays, decreased IQ, and reduced executive function.

This results in increased special education costs to the state, diminished earning potential of children who experience lead poisoning, an increase in unemployment and reliance on unemployment benefits, and an increased likelihood of engagement in criminal behavior, resulting in increased costs to the criminal justice system. A Pew Research Institute study found a $17-1 return on investment for childhood lead poisoning prevention measures. Unfortunately, in the state of New Hampshire, property owners are not obligated to take any action to prevent exposure to a lead hazard until a child has a confirmed laboratory test showing an elevated blood lead level (EBLL) that exceeds five micrograms/deciliter (mcg/dL).

Testing for elevated blood lead levels: Universal testing is required at well-child check-ups for children ages one and two, though a parent can choose to opt out of having their child tested. This testing must be covered by insurance to same as “any other similar benefits provided by the insurer,” and is fully covered by Medicaid. RSA 415:6-v.

Children’s blood lead levels (BLL) are measured in micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL). Children who have unusually elevated levels of lead in their blood are deemed to have an “elevated blood lead level” (EBLL). In New Hampshire, children on average have a BLL of 2 mcg/dL. In 2019, SB 247 was passed by the state legislature to provide additional protection for children. Most notably, it changed the point at which action must be taken to protect a child. If a child has an EBLL of 3+ notification and information regarding the risks of lead poisoning is sent to the parent and to the owner of the property where the parent lives in cases in which a child lives in a leased home. RSA 130-A:6-a. A level of 5 mcg/dL triggers an investigation by DHHS. RSA 130-A:5, I.

Tenant rights: It is generally unlawful to evict a family simply due to the presence of a poisoned child in a unit. RSA 130-A:6-a, II (a). The law sets forth specific protections for tenants, but they come with limits.

Drinking water: Though secondary to lead paint, lead in drinking water still contributes to lead poisoning. Public data is widely available for lead in drinking water for schools and childcare programs. See the following link for testing data. https://www.des.nh.gov/water/drinking-water/lead/schools-and-child-care-programs/view-results.

Stormwater Utility: What, What, Why, and How?

Renee L. Bourdeau, Geosyntec Consultants, Inc.

Attorney Jennifer R. Perez, City of Dover

Attorney James J. Steinkrauss, Rath, Young & Pignatelli, PC

What is a Stormwater Utility? A stormwater utility is a dedicated funding mechanism that provides a stable source of revenue to finance stormwater and flood resiliency infrastructure installation and maintenance. However, unlike a traditional water or sewer utilities charged through metered use, a stormwater utility typically calculates the fees based upon the estimated flow of untreated stormwater runoff generated by a property over impervious areas. The fee is therefore directly related to the amount of impervious areas on the property.

What is required by NH law? The state legislature passed Title X, Chapter 149-I:6 in August 2008 to allow for the creation of stormwater utilities and stormwater utilities commissions in New Hampshire. A stormwater utility or fee must be directly related to stormwater management costs for the following purposes: flooding and erosion control, water quality management, ecological preservation, and managing annual pollutant loads contained in stormwater. Stormwater utilities do not need to be limited to municipal boundaries but can be regional and subject to inter-municipal control and management by a stormwater utility commission. Fees are typically based upon an equivalent residential unit or the average impervious area for a single-family property in a town or city that sets the basis for fee calculations. Stormwater utilities must charge government and non-profit owned properties but must also offer credits and abatements to offset charges that are typically used to incentivize low impact development and implementation of other best management practices by property owners.

Why have one? 1. Stable funding that is separate and apart from general tax funds, 2. Increased costs for implementation of stormwater maintenance, 3. Fair and equitable fees based upon the service costs for treatment of stormwater runoff for all stormwater system users, and 4. Credits to incentivize private investment in best management practices.

How did the City of Dover Develop a Stormwater Utility? In August of 2020, the City Council adopted a resolution to establish the Ad Hoc Committee to Study Stormwater and Flood Resilience Funding. The Committee was formed and consisted of a wide range of stakeholders within the community including business owners, professional engineers, and developers, and received staffing support from the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Coastal Program, Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership, University of New Hampshire Stormwater Center, and the New England Environmental Finance Center. The Committee held 14 meetings from November 2020 through January 2022. In January 2022, the Committee recommended that the Council pursue a stormwater and flood resiliency utility. The Council accepted the recommendation of the Committee and has tasked City staff with the development of a Stormwater Utility, which City staff is now engaging in over the next two years.